If you click on a link and make a purchase we may receive a small commission. Read our editorial policy.

Slaughterhouse-Five, Cat's Cradle and other books from Kurt Vonnegut are beloved classics, and now his lost board game has been rediscovered for the world to play

At PAX Unplugged 2024, Popverse spoke to Geoff Engelstein, who uncovered and publicized the long-shelved Kurt Vonnegut-designed board game, GHQ

Popverse's top stories of the day

- Halloween villain Michael Myers was the key to licensing Dead by Daylight's many killers, says the game's director

- MEMBERS ONLY: For Your Consideration: Columbo, Quincy ME, and The Rockford Files walked so Rian Johnson's Poker Face could run

- WATCH NOW: Baldur's Gate 3 stars Jennifer English and Aliona Baranova go full-on squirrel with Popverse

It sounds like the beginning of a literary thriller: one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century creates a piece of obscure art then shelves it, tucking it away from the world until a determined expert connects the dots to uncover it. But this isn't fictional - it's a board game created by iconic humanist and sci-fi author Kurt Vonnegut called General Headquarters (or "GHQ") - and that determined expert is very much a real person. We know because we talked to him.

Game designer and Geoff Engelstein first came across records of a mysterious Vonnegut-designed board game over a decade ago. A fan of the Slaughterhouse-Five author's work, Engelstein decided to pursue the idea, delving into Vonnegut's history and even connecting with his family in order to bring the idea into the world. Cut to the present day, when Vonnegut's once lost work is now available on shelves across America, entirely because of Engelstein's dogged pursuit.

At PAX Unplugged 2024, Popverse had the chance to hear from Engelstein's own mouth how GHQ went from sunken treasure to rocking the boat of the board game market. In our extensive conversation, we covered Engelstein's investigation, the lows of Kurt Vonnegut's career, and how Engelstein believes the game influenced Vonnegut's later works. If you're a fan of those works, you won't want to miss this one.

Popverse: First question - have you ever referred to yourself as the Indy Jones of the Indy games?

Geoff Engelstein: Well, the number of times I've been asked that question is just staggeringly large.

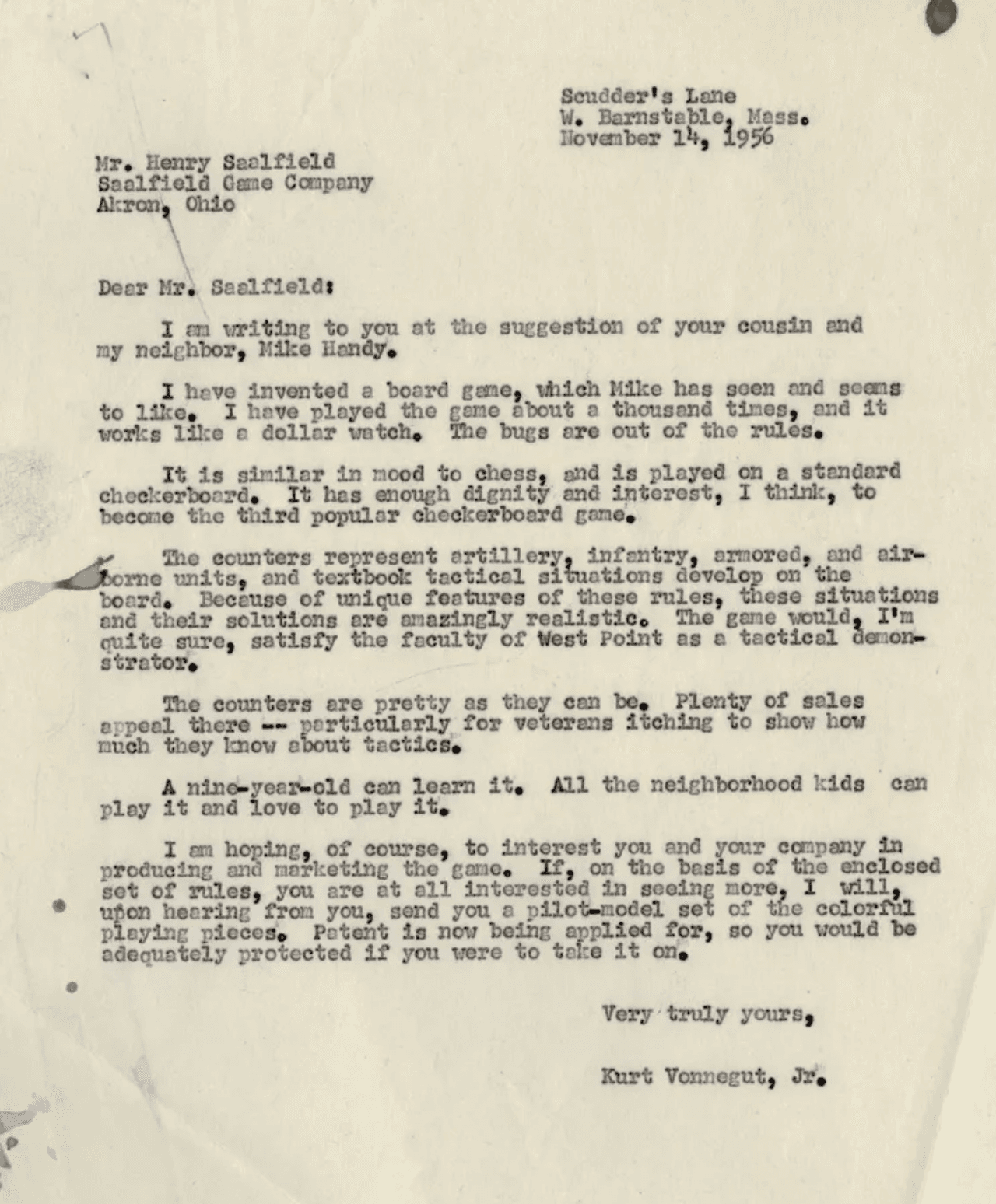

Great answer. Alright, so Kurt Vonnegut’s GHQ is lost in 1956. Before we talk about how you found it; how was it lost?

I wouldn’t say it was so much ‘lost.’ It was with his papers, just put away. It was designed between 1956 and 1957, but it got rejected. So he got the rejection letter, and his father passed away within like a week.So from that, I think he was just disillusioned with the whole thing. He just boxed it up and put it away in his house with his papers.

Just this morning, actually, I was speaking with his son Mark - who was like 8 or 9 years old at the time, and play tested [the game] - and I said, ‘I'd never ask this question before, but did your father ever bring it back up? Or want to bring it out again or revisit it or anything?’ And he said that he never he never looked back, never took it out again.

But Mark knew about it.

He knew it, yeah. He remembered it very fondly. They had spent a lot of quality father-son time testing, and so he was the main play test partner at the time. To help test the game into the game and stuff like that.

That's one thing that's been really super gratifying in this project, starting at the end and working backwards. When I sent [Mark] the first production copy, he reached out to me basically in tears and said that this was just and this long held dream of his father's. He's so excited that it's finally come to fruition. I was expecting [the game] to just be, you know, tangentially associated with Vonnegut in a very, very minor footnote kind of way.

But it was not like people were searching and searching and searching for the papers. I mean, Indiana University had cataloged it and it was mixed in with his other papers. When I reached out to them and said, ‘Hey, is there anything about this board game?,’ they said, ‘Yeah, but we can't show you anything.’ So they knew they had it, but, they were not allowed to release anything without permission from the family.

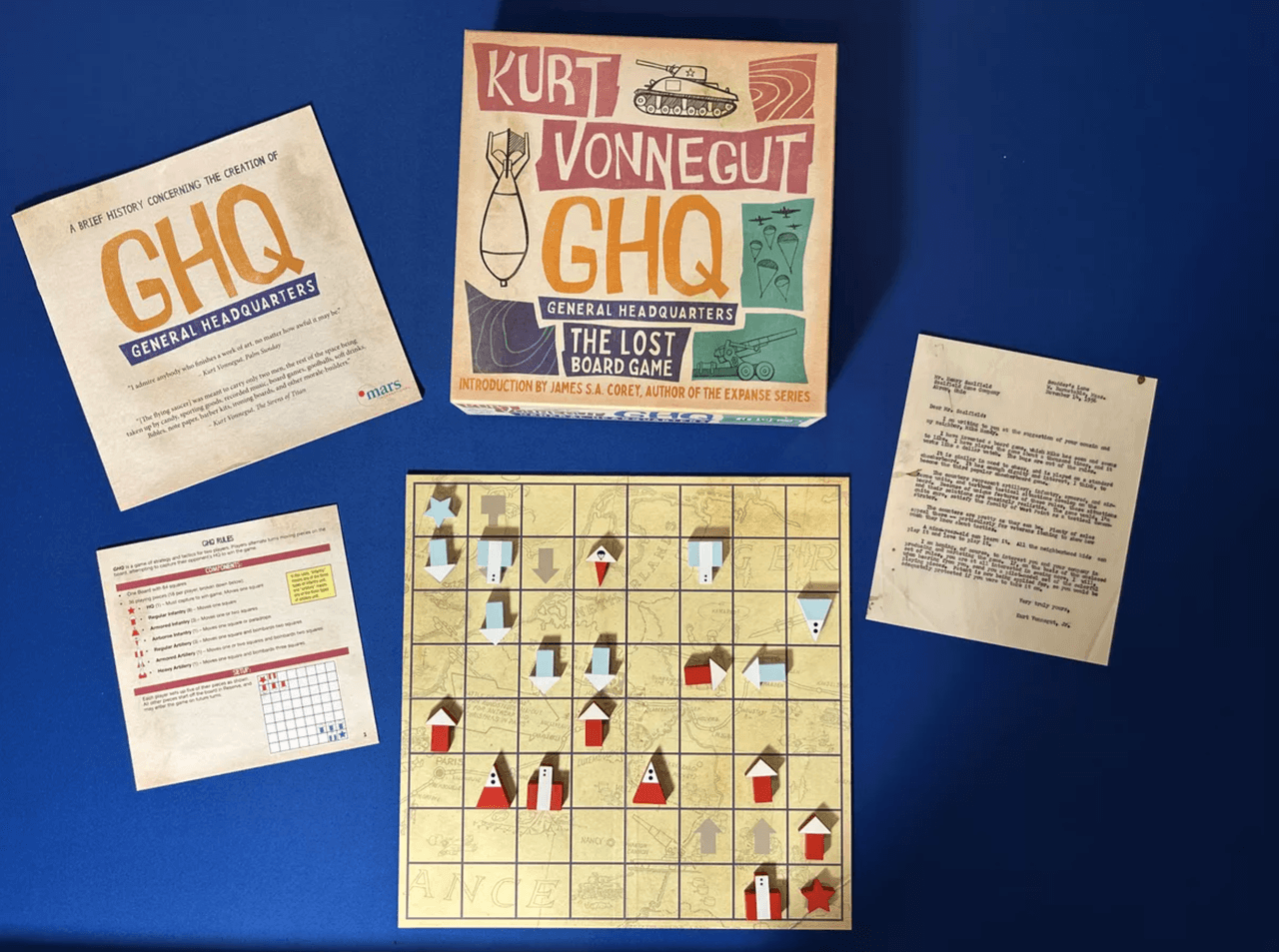

Now that it’s published (or at least, the design is complete). Has Mark said anything about the visuals of it? Are they similar to what he and his dad played?

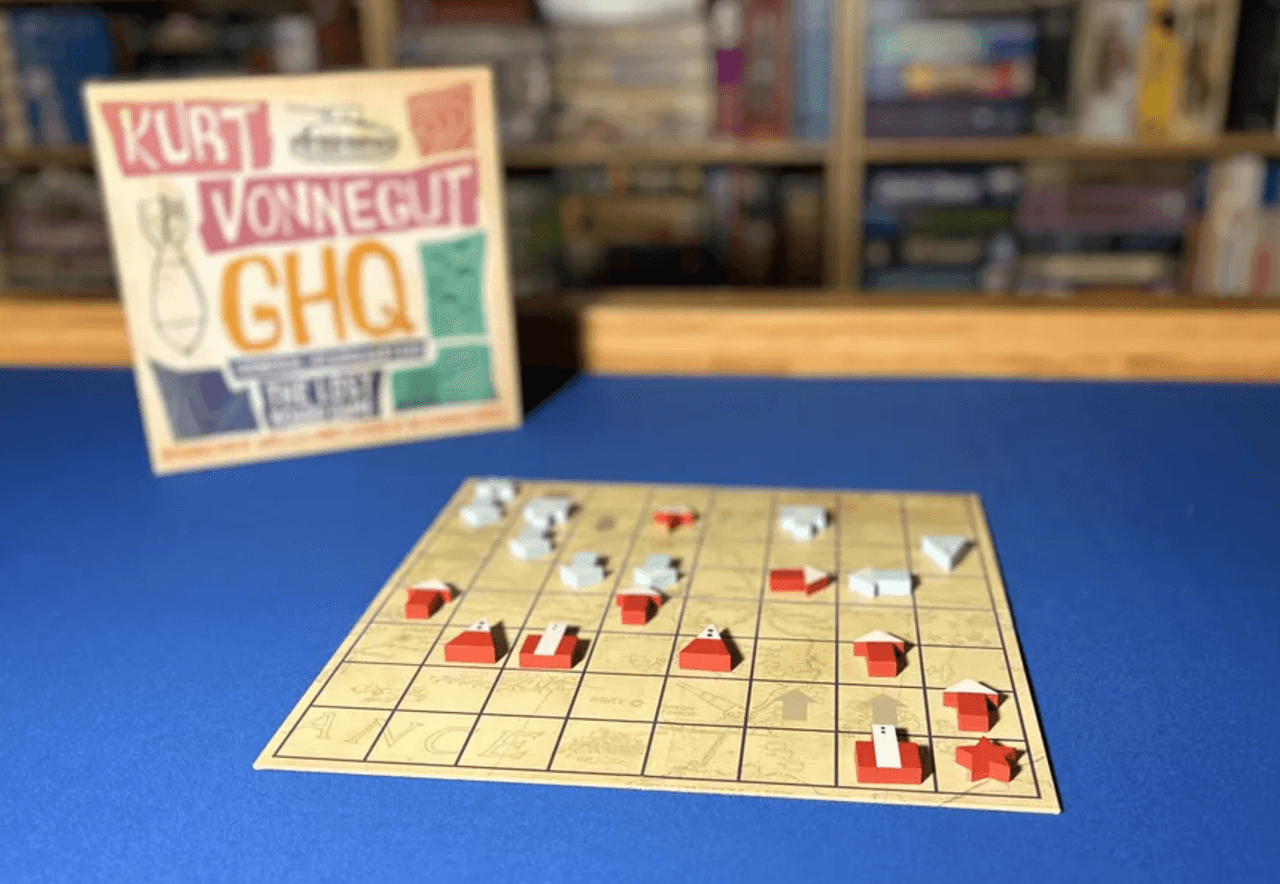

Well, their board was just a plain checkerboard, so we put a little artwork on the board.

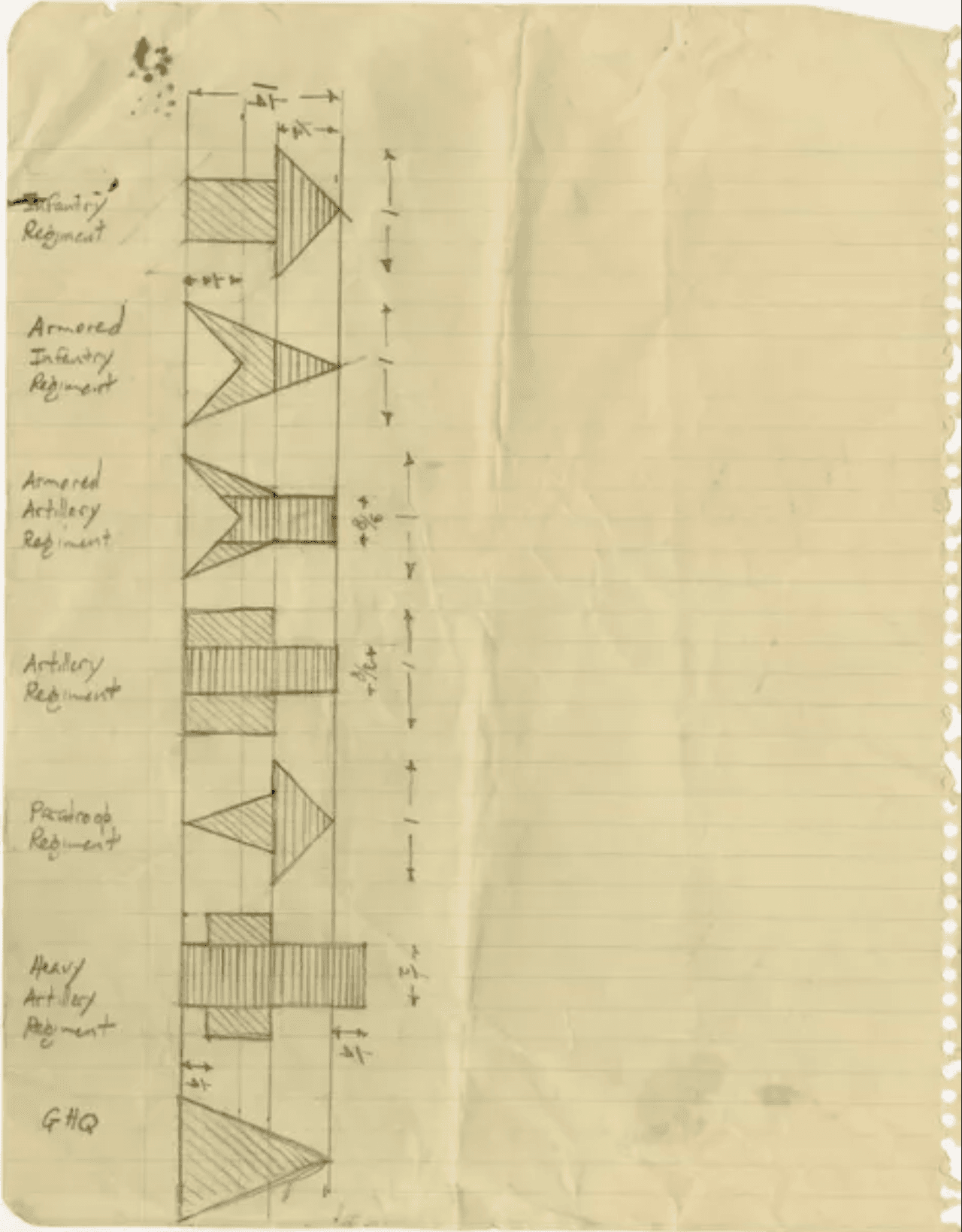

The family still has the original pieces. They found them in the attic or something, and they actually showed me pictures of them, so we went off of that. The family also had drawings of the sketches [Vonnegut] made originally, although he changed them later.

But you could see just from his notes what the pieces were supposed to look like, so we really followed that. We made a few tweaks for playability. Some icons on the pieces and stuff like that to indicate how they move. But, generally, we really tried to follow the esthetics that he had.

Very cool. So backing up now, what was your relationship to Vonnegut before doing the work to unearth his game?

I was always a big fan of his. I read all his books in high school, and he also came to my college. He came in the mid 80s and gave a lecture, so I went to that. That was very cool to see. I mean, it was in a big auditorium and I didn't actually meet him or anything like that.

But, you know, I've always been a fan of his. I was reading a… biography or article? Something about Vonnegut - I wish I could remember what it was - and it just mentioned in passing that, in the 1950s, he designed a board game called GHQ and it never got published. That was it.

No description?

No description, nothing. This is like 2011, something like that. He had passed away in like 2007. So I started poking around, and there was nothing else on the internet except for those two sentences just repeated. Like a folk legend or something.

Finally I found out that all his papers were at Indiana University, and I was able to get it for their archives and get in there and talk to the right people. And they went back and they acknowledged that they did have some stuff that was classified as working materials. But like I said, they couldn't show anything to me.

I finally found out who I needed to contact, who was running the estate at that point. That was his old lawyer/agent, whose name was Don Farber, who lived in Manhattan and was, oh, I guess he was in his, like, 80s, early 90s when I, when I talked to him first.

He was just like the quintessential New York entertainment agent lawyer. I get him on the phone and he's just like, ‘Vonnegut would have been nothing if it wasn't for me!’ He since has passed away also.

So I talked to him and explained what I wanted to do, and we had to talk a few times where before I convinced him that I was in it for the right reasons. Then I was at work one day and just into my email inbox comes this 50-page PDF scan of all of his handwritten notes. Vonnegut’s notes, they just showed up. I didn't even know it was coming or anything. And I was like, ‘Well, I guess I'm not getting anything else done today.’ As far as I'm aware,I was one of the first people to really see these since the 1950s, certainly as a game designer. Looking at it from that aspect was just unbelievable. And so was reviewing and putting together the story of how the game was because it was all jumbled together. There's no dates on most of it. So I had to really go through and try to figure out, chronologically, what had happened. It was like 5 or 6 different versions of the rules in his letters.

Then the bonus was, when I finally figured out how to play the game, it was actually pretty good.

Did you get a lot of the Vonnegut style in his notes? The Vonnegut humor and satire; did you find that in there a lot?

Not the satire so much, but absolutely. Like in the drawings, there's a lot of his handwritten doodles. The thing that really blew me away, that I think is absolutely his style, is the pitch letter that he included with the game. That's been out there now, I've been publicizing that because I just love that that was, you know, it was like the second to last page in the document package that I got. So I read it super late. And then when I read this, I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is amazing.’ To the point where, in the game, when you open the box, the pitch letter is the first thing you see. It's as if he's pitching the game to you, right? So it's kind of this archive. The style of this is very much it's him all over you know it's him.

So that was one of the main places. The other place where it came up was in some of the sketches that he did, some of his notes about the game where he's trying to figure out how to phrase things. He actually did little engineering drawings of the pieces that he wanted to change later. Then later, once he started getting into the more serious versions of the rules, he drew these little fluffy smoke clouds, which if you’ve ever seen, like any of his novels, are on the covers of Breakfast of Champions or even Slaughterhouse-Five. I mean, it's vintage him.

[Editor's note: Read that pitch letter below.]

The thing that really stuck out for me is that, you know, it's a war game. There's no irony in it at all. It's not tongue in cheek. He's like, ‘You could take this to West Point and train people on tactics.’ And it's good for veterans who are looking to show what they learned in the war. That's part of his pitch of the whole thing.

Where do you think that comes from? Because Vonnegut was so anti-war.

There's no evidence for this, but just my feelings about it is are: He was in the war, from like 1944-45. Slaughterhouse-Five came out in 1965, and this game is 1955-56. It’s right smack in the middle. I think he was on a journey in terms of internalizing or coming to grips with how he processed his war experiences.

Like, Slaughterhouse-Five was the very first book he ever wanted to write. And he started and stopped it 4 or 5 times before he finally kept writing it. It wasn't good enough, it wasn't doing what he wanted it to do, and he put it away. He had to write all his other novels and come up with his voice before he was able to write it. I think that this game, in a way, was part of that process of him writing Slaughterhouse-Five and not being able to do it.

Stepping away from Vonnegut himself, I wanted to talk about when you first pitch this to Metatopia, what was their reaction?

When we finally reconciled those different versions of the rules, I thought it was pretty good, but I wanted to get some unvarnished opinion. So in New Jersey, there's a so-called Metatopia convention conference. So I made up little paper pieces - I didn't cut them out of a jigsaw like he did - and I just put it in front of people. And I was like, ‘Try this two player game.’ And people kind of liked it. So that was, you know, that was a litmus test for me.

In [Vonnegut’s] letter, he says, ‘I think it's going to be the third great checkerboard game.’ I don't think it is the third great checkerboard game; I don't know what a third grade checkerboard game is. But there was definitely something there.

There's only a few things I had to tweak as far as from ambiguities and stuff like that. 99% of it is what he designed. So that's what gave us confidence to say, ‘Hey, this is really something, maybe we should publish it.’

Speaking of people finding value in GHQ, the into to the game was written by James S.A. Corey, of The Expanse fame. Yep. How did that come about?

That's a pseudonym for Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck. I had designed, in 2020 or something, The Expanse game for them, so I had a relationship with them. You know, The Expanse started as a roleplaying game that they I did. I don't remember what system it was, in that they made up their own. Eventually they were like, ‘Oh, this is cool. We should write a novel of this.’ So I just felt that they were a perfect fit for it.

And I had their address. That’s half the battle.

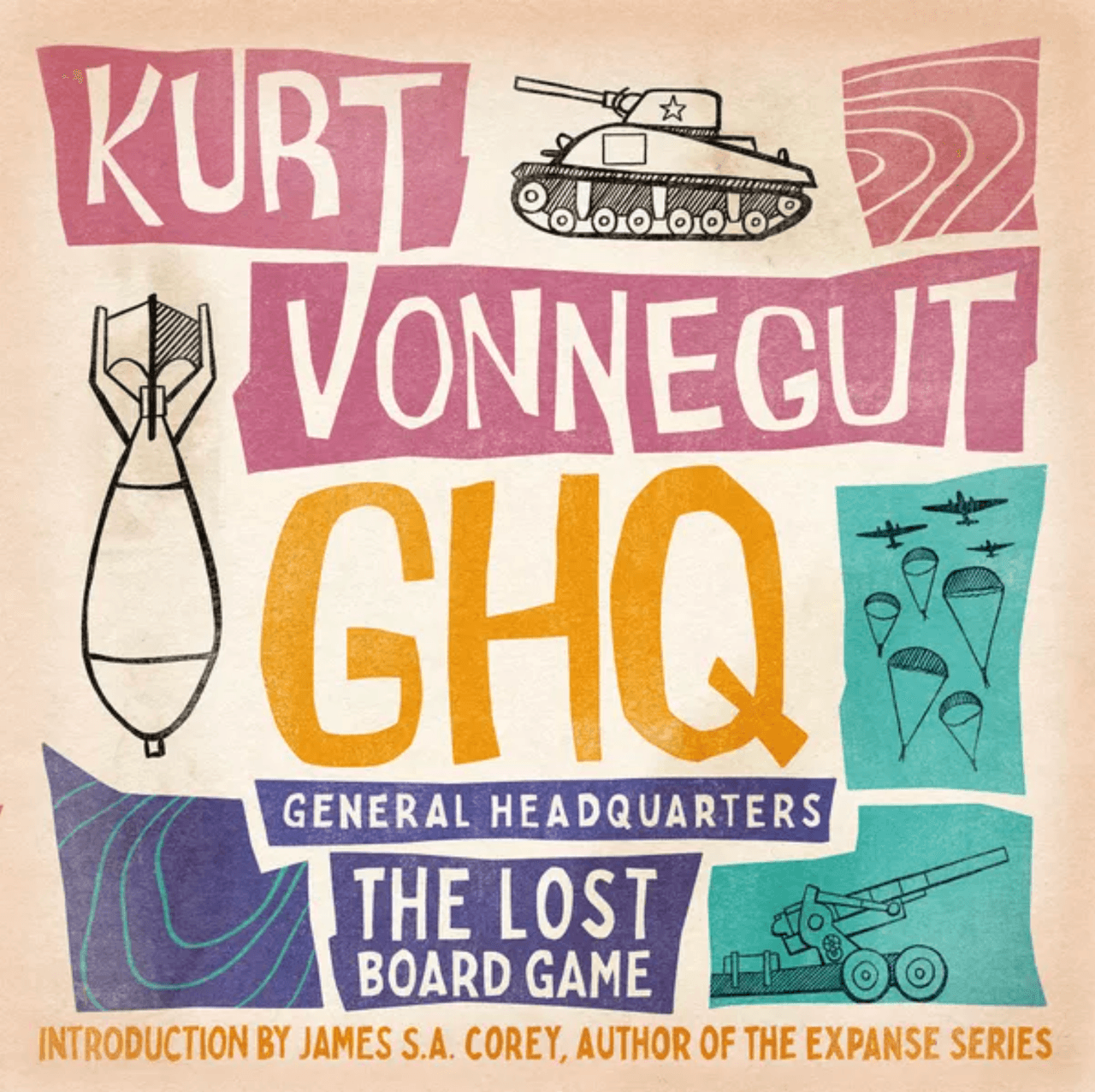

Finally, you’ve said you wanted people to know about the work that went into creating the art for the game, the cover. Can you speak to that?

We wanted to do right by [Vonnegut] and by the fans and by the history and his legacy. Right? So even if he's, like, made a war game, it’s in the 1950s, we thought putting some tanks and some infantry shooting at each other on the cover didn't make sense for him. So we tried a bunch of different things.

First, we tried these ultra modern covers, just like stark white with maybe some silhouettes or some doodles that kind of copied his doodles. That just wasn't really working. Eventually we kind of hit on this idea of like, ‘Let's make it look like it was made in the 60s.’

The artist, who is really getting annoyed me at this point, did a whole bunch of covers like based on that, which also looked awesome, but, you know, they just weren't right. Finally, I went out and started talking to some other artists, and one of them just sent me this pop kind of book cover that was not from the 60s, but it was reminiscent of that. It had just come out. It was trying to mimic this old style, and I was just like, ‘Oh my God, this is perfect.’" It just lit a fire, you know?

So I went back to the artist like, ‘Oh, yeah, that's let's go with that.’ And that ultimately is where it had sort of that it's 60s sort of feel, like it came out in the 60s. But at the same time it's kind of modern. It's got his doodles. I mean it was just super. It's just been a very cool project to work on; it's been interesting. And now there’s this whole other project that Stephen Sondheim, that's a whole other story.

…what?

Stephen Sondheim also just made a board game when he was in his 20s, before he was famous, and he never went anywhere. His mother drew all the parts for him and everything, and then he tried to pitch it.

How frequent is this, that somebody pitches a board game before they go on to redefine a different art medium?

That’s kind of my new niche, but that is actually a really fascinating story. When I talked to The New York Times, I pitched them both things as a combined article, and they ended up chucking all Sondheim stuff. But if you're looking for an article, this on that story is real.

Oh believe me, we’ll be following up on that.

GHQ is available to order through Barnes & Noble now.

Want to know what's coming up next in pop culture? Check out Popverse's guides to:

About Pax Unplugged 2024

PAX Unplugged is a tabletop gaming-focused event specifically tailored to lovers of board games, RPGs, miniatures, cards, and more. Featuring thought-provoking panels, a massive expo hall filled with the best publishers and studios, new game demos, tournaments, and a community experience unlike any other.

Dates

-

Location

Philadelphia

United States of America

Follow Popverse for upcoming event coverage and news

Find out how we conduct our review by reading our review policy

Let Popverse be your tour guide through the wilderness of pop culture

Sign in and let us help you find your new favorite thing.

Comments

Want to join the discussion? Please activate your account first.

Visit Reedpop ID if you need to resend the confirmation email.